From Outer Heaven to Shadow Moses: My Metal Gear Retrospective

I’ve played Metal Gear Solid 1, Metal Gear 1, and Metal Gear Solid 4 before, but after watching a bits and pieces of a full playthrough on YouTube, I got the itch to revisit everything properly, in order.

This time, I started from the very beginning by replaying Metal Gear and finally trying out Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake on the PS5 via the Metal Gear Solid: Master Collection Volume 1.

I had previously finished Metal Gear via the PS3 version of the collection, and had attempted Metal Gear 2, but initially was lost as to the difference in gameplay mechanics from the previous entry.

What began as nostalgia quickly turned into an appreciation for just how much of Metal Gear Solid’s DNA already existed in those early games, especially Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake.

Metal Gear (1987): The Starting Point

The original Metal Gear is primitive by modern standards, but you can already sense Kojima’s ambition. You play as Solid Snake, a rookie operative sent into Outer Heaven by Big Boss, only to learn he’s been manipulated and tricked by the very man giving him orders. For a late ’80s action game, that twist was ahead of its time.

The gameplay is simple and the bosses come and go without much buildup, but the themes are there: deception, betrayal, and the cost of following orders. Even back then, Kojima was setting the tone for everything that would follow.

One thing I’ve always loved about the series is its habit of ending with a tease. The original Metal Gear is no different as after you defeat Big Boss, he vows revenge, a generic villain line at the time, but The Phantom Pain later recontextualizes it. The Big Boss you kill here isn’t the real one at all, but Venom Snake, his body double. Suddenly, that 8-bit revenge promise becomes an interesting connection to future Metal Gear games.

Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake (1990): The True Foundation1

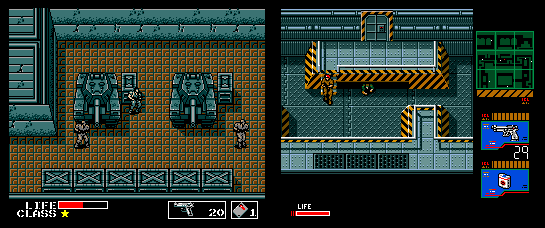

Metal Gear 2 feels like the missing link between the 8-bit era and the cinematic Metal Gear Solid. The leap in design from MG1 to MG2 is astonishing: you can crawl, knock on walls to distract guards, use sound and vision to your advantage, and even account for how different floor materials make noise. In the original you could only hide behind walls or in a cardboard box to hide yourself from view.

It’s also the game where many of the series’ most recognizable figures first appear. Colonel Campbell and Master Miller make their debuts here, establishing the support structure that would become a staple of the Codec conversations in MGS1 and beyond.

Snake infiltrates Zanzibar Land, a heavily armed nation built under Big Boss’s command. Unlike in MG1, it’s made clear early on, through dialogue after Snake’s first boss battle, that Big Boss is the force behind this new military power. The story digs deeper into the emotional side of Snake’s mission, hinting at the more human and introspective tone Kojima would later perfect.

What struck me most is how many minor gameplay features of Metal Gear Solid already exists here: frozen rations, a key that changes temperature, cybernetic ninjas, and expanded Codec chatter, it’s all here, waiting to be reborn in 3D nearly a decade later.

The first boss Snake encounters in MG2 is a familiar face: Schneider, the former resistance leader from MG1. After the fall of Outer Heaven, NATO launched a bombing campaign that wiped out nearly everyone involved, resistance members and Outer Heaven soldiers alike. In the chaos, the real Big Boss appeared and, surprisingly, helped the survivors escape. Schneider was among those saved, barely making it out alive. In MG2, he returns under a new identity: the Black Ninja. Following the events of Outer Heaven, the backstory of Schneider mentions that he joined a top-secret unit and was later equipped with experimental armor and reflex-enhancing drugs. When the program was shut down, he and the remaining members defected to Zanzibar Land.

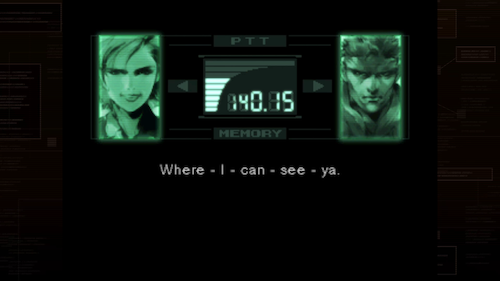

As the mission continues, Snake meets Holly White, a CIA operative posing as a journalist inside Zanzibar Land. Her witty, flirtatious banter with Snake mirrors the dynamic he’d later share with Mei Ling in MGS1, adding rare warmth to his otherwise stoic personality. By the game’s end, Snake promises Holly a dinner that never happens, and after the credits, Campbell and Holly reveal he’s vanished following the decoding of Dr. Marv’s disk.

Having retreated into the wilderness, Snake isolates himself in Alaska, unable to face the life he’s led. Though never stated outright, it’s implied that the trauma of killing Big Boss, whom he learned was his father, and the weight of his actions have driven him into that self-imposed exile we see at the start of MGS1. His sudden departure in the context of this game is odd given that the game doesn’t make it explicit that he learns that Big Boss is his father, which was introduced in Metal Gear Solid 1 during a codec conversation between Colonel Campbell, Snake, and Naomi. This makes the scene of Snake just leaving more odd.

Besides Holly, Snake meets another key character, Gustava Heffner, by sneaking into the women’s restroom, a moment Kojima would later reimagine with Meryl in MGS1. Encounters like these give MG2 a sense of continuity and evolving design philosophy, showing how Kojima was already experimenting with emotional storytelling and gameplay concepts, making Metal Gear Solid 1 even more of an evolution of Metal Gear 2.

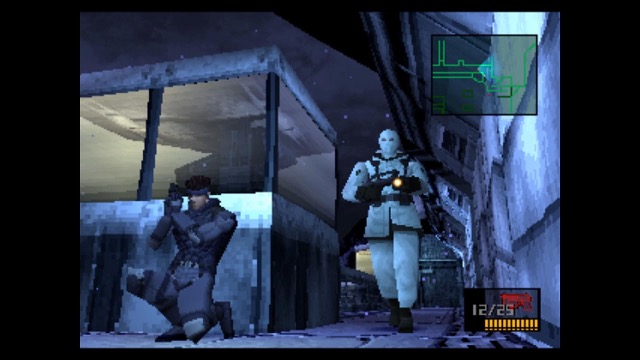

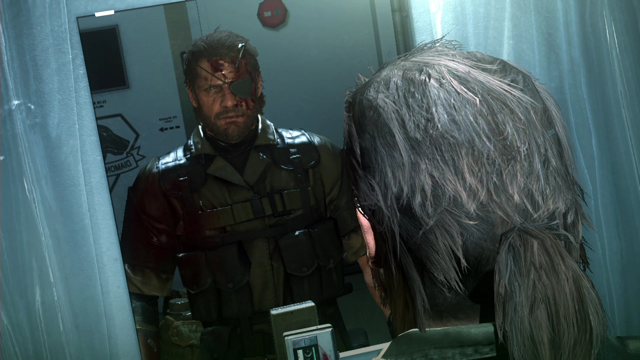

Metal Gear Solid (1998): Stealth Becomes Cinema2

Jumping from Metal Gear 2 to MGS1 feels like going from prototype to masterpiece. The gameplay loop is nearly identical, infiltrate a base, face eccentric bosses, unravel conspiracies, but now it’s fully voiced, cinematic, and emotionally resonant.

What I love about MGS1 is how it gives each boss a unique backstory. Psycho Mantis, Sniper Wolf, Vulcan Raven, they’re tragic figures, not just obstacles.

In the MSX games, villains were mostly nameless soldiers. Here, they’re fully realized characters, participating in the events on Shadow Moses for their own reasons.

Much like the classic Metal Gear games (from the MSX and NES), MGS1 ends with another twist. The post-credit call between Ocelot and the President reframes everything, planting seeds for MGS2. It’s self-contained yet suggestive of what’s to come, the perfect ending to a perfect arc.

From Big Boss to Phantom Pain

Even though I’ve yet to play MGS3 and Peace Walker to completion, and have paused The Phantom Pain until I eventually finish MGS2 and 3, revisiting the early games has already deepened my appreciation for how these later titles expand the saga.

From what I understand, Peace Walker introduces key figures like Paz, Huey (Otacon’s father), and Master Miller (explaining his later relationship with MG’s Snake), while exploring the rise of Big Boss’s private military organization, all elements that become central in The Phantom Pain.

The Phantom Pain’s major twist, revealing that the player is actually controlling Big Boss’s double, Venom Snake, tries to tie everything back to the original MSX titles. It reframes the entire series as a generational tragedy of loyalty, deception, and legacy.

Reflections on the Early Games

Playing the MSX titles today is a test of patience, especially if you attempt the NES version of Metal Gear, which has its share of quirks and problems not present in the MSX-version.

The controls can at times feel stiff in the MSX versions, the Codec advice in MG2 becomes repetitive (particularly from Master Miller), and the storytelling can occasionally veer into clumsy. But beneath that, you can see the framework of a legend forming. Kojima’s attention to detail, guards reacting to footsteps, temperature-based mechanics, meta-commentary through radio chatter, was already genius for the early 1990s.

I also found it fascinating how MG2 foreshadows elements Kojima would later refine:

- Schneider becoming the Black Ninja prefigures Grey Fox.

- The frozen rations and key mechanics resurface in MGS1.

- Snake meeting a female ally in a women’s restroom.

- Fighting a Hind-D (which happens in both MG1 and MG2).

- Mechanics like knocking on walls to lure guards, hiding underneath objects, both were introduced in MG2.

Even the structure of MG1 and MG2, a lone agent infiltrating a fortified base to destroy a walking tank, remains unchanged throughout the series. MGS1 didn’t reinvent Metal Gear; it simply perfected what came before it.

Final Thoughts

If Konami ever remakes Metal Gear and Metal Gear 2, I hope they preserve the emotional throughlines that elevate these games beyond historical curiosities, Snake’s silence, Big Boss’s ideology, revelations like Schneider’s return, and the complicated bond between Snake and Gray Fox. These elements deserve modern treatment and deeper exploration, especially Gray Fox, whose arc feels rich but underdeveloped by the limitations of the era.

Revisiting the early titles is a reminder that Metal Gear was never just about stealth. It was always concerned with identity, manipulation, legacy, and the ghosts of past selves. Kojima was already telling that story in 8-bit pixels, long before the series had the technology or cultural context to fully articulate it. With the benefit of hindsight and the full saga in view, it is clear that the foundations of Metal Gear Solid were not built on polygons or voice acting, but on ideas, ideas that would echo throughout the series for decades.

One lingering mystery surrounding the franchise, beyond its famously convoluted plot twists, is why it has never successfully made the jump to film or television. Given how deeply Kojima’s love of cinema shaped Snatcher, Policenauts, and Metal Gear, the absence of a definitive screen adaptation feels strange. This is especially true considering that David Hayter, the longtime voice of Snake (setting The Phantom Pain aside), is also an accomplished screenwriter. With themes that remain politically and culturally relevant, Metal Gear feels uniquely suited for adaptation, making the lack of a realized film or series seem like a missed opportunity.

| Character | Actor(s) |

|---|---|

| Solid Snake | Mel Gibson |

| Roy Campbell | Richard Crenna |

| George Kelser | Dolph Lundgren |

| Madnar | Albert Einstein |

| Big Boss | Sean Connery |

| Yozev Norden | Bob Hoskins |

| Holly White | Brenda Bakke |

| Grey Fox | Tom Berenger |

Although Kojima wasn’t involved in the illustration, the front cover of the original Metal Gear apparently used a publicity still image of Michael Biehn as Kyle Reese (Terminator) for Snake.

-

An interesting note about the original Metal Gear games as they are in Metal Gear Solid: Master Collection Volume 1 is that the profile pictures for the characters were changed to match the look of characters like Snake as they appear in Metal Gear Solid. ↩︎

-

A playthrough of the MSX version of Metal Gear 2 shows how similar some of the characters look to actors: ↩︎